Sun then set, and shade

Sun then set, and shade

All ways obscuring, on the bounds we fell

Of deep Oceanus, where people dwell

Whom a perpetual cloud obscures outright,

To whom the cheerful sun lends never light,

Nor when he mounts the star-sustaining heaven,

Nor when he stoops earth, and sets up the even,

But night holds fix’d wings, feather’d all with banes,

Above those most unblest Cimmerians.

– from Homer’s Odyssey, trans. George Chapman (Book XI)

Immediately after, Odysseus arrives at the dusky entrance to the Underworld.

The real people of Cimmeria (pronounced and sometimes spelt Kimmeria) are almost as cloaked in mystery as their land is in Homer. It is hard to find decent, non-racially motivated or Conan-related material on the internet about the Cimmerians. I use ‘Who were the Cimmerians?’ by Tim Bridgman for much of my information.

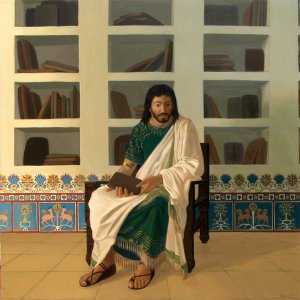

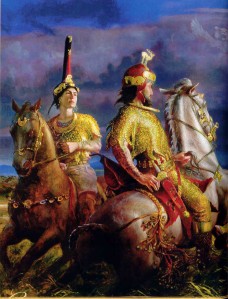

The first mentions of these ancient people (who existed largely from the 8th to 7th centuries BC) are in Assyrian texts. They are depicted as a powerful and mobile military threat to the Assyrians and to the proto-Armenian empire of Urartu. Durnig the 7th century, the great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal writes of a Cimmerian enemy. Ashurbanipal is known for collecting a vast library at Nineveh (which includes the Epic of Gilgamesh), for his popularity and for his cruelty to enemies (including putting a dog-chain through an enemy king’s jaw and forcing him to live in a kennel).

Ashurbanipal has some stern things to say about his Cimmerian enemy, a leader called Tugdamme. Ashurbanipal’s inscription is found in Babylon and addressed to the god Marduk:

Tugdamme…disregarded the oath of the gods…not to sin against the border of my land, and he was not in awe of thy honoured name. I overthrew him, according to your divine message which you did send, saying: ‘I will destroy his power’.

Being a mighty Assyrian, I’m sure he probably destroyed Tugdamme. The Cimmerians didn’t have all that much luck, historically.

No one is quite sure of the Cimmerians’ origins but with a little help from Herodotus, we can piece together a narrative. The Cimmerians were probably a settled people, not nomads, and lived around the northern Black Sea area. The Cimmerians moved south across rivers, across the Caucasus and harried the borders of the Assyrian and Urartian empires. But the Scythians of the east ultimately expanded into the Cimmerians’ home territory and drove them away, perhaps assimilating some of them in the process.

Before the Cimmerians lost their homeland to the Scythians, Herodotus describes how the leaders chose not to flee with the rest. Instead, they fought with each other in equal numbers until all had slain each other. That way, they could all die and be buried in their native soil.

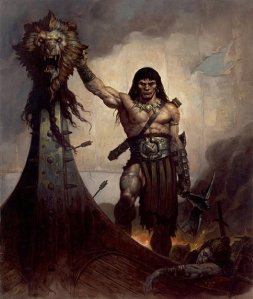

It is possible, although not universally accepted, that Cimmerian migrations after the Scythian expansion led to the Cimmerians moving much further into Europe and making them ancestors to Celtic or Germanic people. It is possible this connection was in Robert E. Howard’s head when he created his own version of the Cimmerian people, the barbarian race of Conan. Howard’s Cimmerians live in harsh, gloomy and mountainous conditions. They are uncivilized but they are generally noble and just.

Perhaps Conan isn’t all that bad a way to at least start remembering the Cimmerians, since we have such meagre historical/archaeological evidence of the people. Howard’s Cimmerians and Conan are completely fictional, taking only inspiration from history. But then, so was Homer’s vision of the Cimmeria, right at the gateway to the Underworld. So shrouded in history’s silence and literature’s fancy, I suppose the Cimmerians are better remembered through myth and mist than not at all.

It was so long ago and far away

I have forgotten the very name men called me.

The axe and flint-tipped spear are like a dream,

And hunts and wars are like shadows. I recall

Only the stillness of that sombre land;

The clouds that piled forever on the hills,

The dimness of the everlasting woods.

Cimmeria, land of Darkness and the Night.

– from ‘Cimmeria’ by Robert E. Howard